River Arrival: USU Geologist Explores When the Colorado Met the Sea of Cortez

By Mary-Ann Muffoletto |

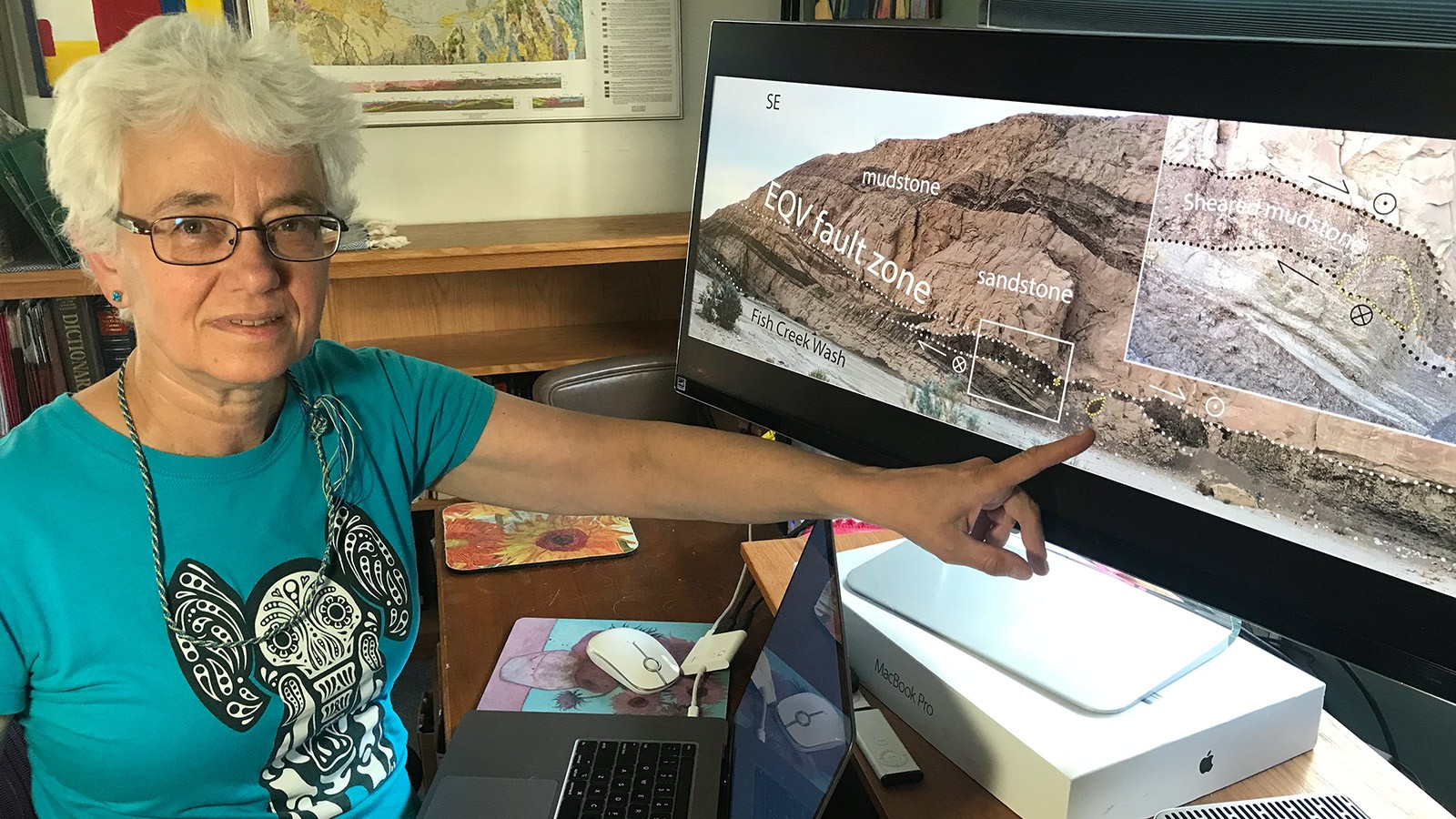

USU geologist Susanne Jänecke documents a small strike-slip fault in southern California's Fish Creek Basin. She and her colleagues’ findings, published in 'Geology,’ shed light on when the Colorado River first arrived at the Sea of Cortez. Jim Evans.

Originating from headwaters in the Rocky Mountains, the nearly 1,500-mile-long Colorado River traverses seven western U.S. states, as it crosses the Colorado Plateau and winds southwesterly toward Mexico’s Sea of Cortez.

Strained by drought and caught in a precarious tug-of-war between competing, unrelenting interests, the river flows through some of North America’s most iconic scenery, including Grand Canyon. Tiny grains of sanidine, pale feldspar crystals from red rock sediments carried westward by the river, are yielding evidence of the aptly named Colorado’s (Spanish for “red-colored”) first arrival at its Gulf of California destination. A multi-institution team of scientists, including Utah State University geologist Susanne Jänecke, report the river’s first encounter with the sea is more recent than once thought.

“Using sanidine dating and magnetostratigraphy – a geophysical correlation technique to date sedimentary and volcanic sequences – we’ve narrowed the timing of integration of the lower Colorado River with the evolving Gulf of California to between 4.6-4.8 million years ago,” says Jänecke, professor in USU’s Department of Geosciences and a GSA Fellow.

With colleagues from the U.S. Geological Survey, University of Oklahoma, University of New Mexico, New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources and Arizona Geological Survey, Jänecke report new insights in the early online edition for the June 2021 print issue of the Geological Society of America’s Geology journal.

The team’s findings challenge previous proposals, including a 2011 paper in GSA Bulletin to which Jänecke was a contributing author. The 2011 paper placed the timing of integration of the lower Colorado River with the evolving Gulf of California closer to 5.3 million years ago. Later proposals suggested the Colorado River reached the Gulf of California twice; once at 5.3 and, again, at 5.0 Ma.

“The Fish Creek Basin in Anza-Borrego State Park preserves the first Colorado River sand to reach the Sea of Cortez, and the area is riddled with many more faults than we appreciated in 2011,” she says. “Improved dating technology and newly identified strands of southern California’s fault zones are helping us resolve a number of timing discrepancies.”

Jänecke, who has studied California’s San Andreas Fault system and areas around the Salton Sea for more than 20 years, says the ability to identify airborne sanidine from ancient volcanic eruptions has many implications. These sanidine crystals, she says, mixed together with sand grains, were carried into the Sea of Cortez shortly after the Colorado River’s first contact with the ocean.

“The rocks with evidence for the integration of the lower Colorado River with the ocean were displaced by the San Andreas fault system to their current position southwest of the Salton Sea, where the work led by USGS scientist Ryan Crow advances our knowledge of the waterway’s fascinating history,” Jänecke says. “My co-authors and others have shown the Lower Colorado River formed as the Colorado River sequentially filled up lake basins that were separated from one another by preexisting natural dams. The river quickly, geologically speaking, incised the natural dams between each lake basin and connected it with the Sea of Cortez.”

The process, she says, set up a “fill-and-spill” process that resembles a tiered fountain with water cascading quickly through a descending series of basins. The final fill-and-spill reached the ocean about 4.6-4.8 million years ago, according to the new paper by Crow et al. 2021.

Critical to the new interpretation was the discovery of faults that expand California’s arid Earthquake Valley fault zone, 30 miles to the southeast. Jänecke says the zone’s faults cut right through the first-arriving package of sands in Fish Creek Basin.

“Those faults duplicate sedimentary rocks and explain the discrepancy between the original and new studies,” she says. “The sanidine crystals tell the story of the river’s history, and also have potential to refine when focused plate motion and basin development started along the southernmost 200 kilometers of the San Andreas Fault Zone.”

View a video created by Jänecke for USU Geosciences’ 2021 Rock-n-Fossil Day, in which she describes faults and earthquakes.

USU Geosciences Professor Susanne Jänecke points out broken blocks of rock within a major fault trace of southern California's Earthquake Valley fault zone, using her figure from a recent paper by USGS scientist Ryan Crow and others. Jim Evans.

USU geologists Susanne Jänecke, center, and Jim Evans, left, collect samples from California's San Andreas Fault Zone. Foreground, a colleague holds a sample revealing striated fault surfaces with bluish coatings of secondary minerals. Robert Quinn.

WRITER

Mary-Ann Muffoletto

Public Relations Specialist

College of Science

435-797-3517

maryann.muffoletto@usu.edu

CONTACT

Susanne Jänecke

Professor

Department of Geosciences

435-797-1273

susanne.janecke@usu.edu

TOPICS

Research 877stories Water 257stories Rivers 101stories Geosciences 74storiesComments and questions regarding this article may be directed to the contact person listed on this page.