Out of Sight & Mind: Quantifying Pervasive Microplastics in the Ocean-Atmosphere Cycle

By Lael Gilbert |

It is projected that 12 percent of all plastic waste ends up in aquatic environments. There is growing recognition that tiny microplastics are moving directly from the atmosphere into the world's oceans and back again in a two-way exchange.

Car tires, candy wrappers, water bottles, takeout containers and toys — our plastic waste adds up.

Considering the millions of tons of plastic produced, used and discarded by humans every year, it’s a bit shocking to note that researchers are just now coming to terms with how much we don’t yet understand about the consequences of this plastic ecosystem, some of which we can’t even see.

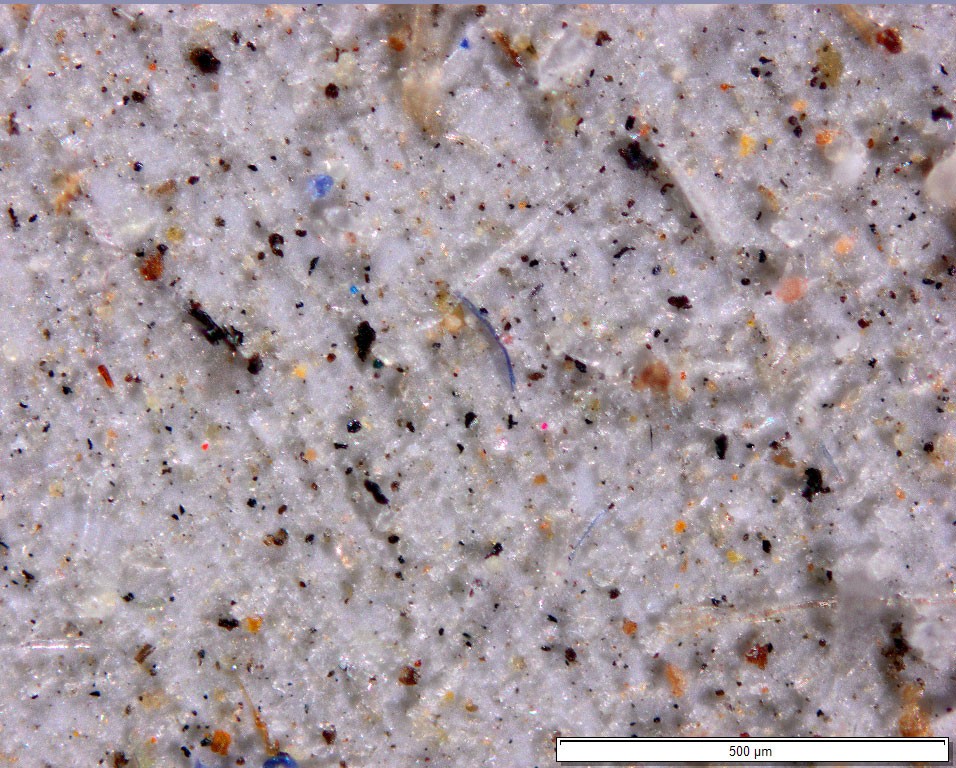

Much of our plastic waste breaks down into microplastics — tiny pieces of plastic that invisibly move into ecosystems.

But researchers haven’t yet been able to measure how much of that material is being pulled into the atmosphere and deposited into the world’s oceans, how much remains floating in the atmosphere for animals to breathe and plants to absorb, how much settles into soil — and what happens to it next. And they can’t yet quantify the consequences of the millions of tons of plastic waste added to this global cycle year after year.

It’s high time to know more, according to Janice Brahney in a new perspectives paper in the journal Nature, and researchers will need to globally cooperate to gather this essential information.

Brahney, from the Department of Watershed Sciences in the Quinney College of Natural Resources, is part of a team of 33 international expert scientists in atmospheric, oceanography and plastic pollution who delineated numerous gaps in knowledge about the global cycle of plastic waste.

It is projected that around 22 percent of our total plastic waste is absorbed into terrestrial environments such as sand and soil, and 12 percent enters aquatic environments like rivers and oceans, according to the paper. But research on the amount of plastic in oceans is primarily focused on relatively slow-moving waste transported from human communities into waterways and then on to the sea.

There is growing recognition that tiny microplastics are moving along another superhighway altogether: directly from the atmosphere into the world’s oceans and back again, in a two-way exchange.

“The atmosphere picks up and moves the smallest microplastics … some the size of a piece of dust or as small as bacteria,” Brahney said, “but air currents are a notably faster way to travel than water, and these atmospheric depositions can reach every part of the planet. Marine air, arctic snow and coastal fog have all been found to carry atmospheric microplastics.”

In coastal areas where seawater laden with microplastic waste is constantly churned by waves and vaporized into the air, microplastics in the water have ample opportunity to reenter the atmosphere and be transported for miles — and then dropped onto soils or redeposited into new parts of a marine environment.

“We know it is happening, we just don’t know how much or how fast,” Brahney said. “Since marine environments extend over 70 percent of the planet, it probably isn’t a small number.”

To combat uncertainty and to advance understanding, the paper outlines a global observation and research strategy to provide a long-term observation network of atmospheric microplastics and help to quantify them.

Projections indicate that if human communities continue under a business-as-usual scenario, plastic pollution will triple by the year 2040. Researchers critically need better information about atmospheric-ocean interactions so that they can identify what sizes of particles are being transferred and in what amounts, so that the system can be understood and measured, Brahney said.

Tiny microplastics move through every ecosystem and transfer between the earth's oceans and atmosphere. But researchers can’t yet quantify the consequences of this global cycle. Janice Brahney and a team of atmospheric experts from around the world hope to fix that.

WRITER

Lael Gilbert

Public Relations Specialist

Quinney College of Natural Resources

435-797-8455

lael.gilbert@usu.edu

CONTACT

Janice Brahney

Associate Professor

Department of Watershed Sciences

435-797-4479

janice.brahney@usu.edu

TOPICS

Environment 263stories Water 257stories Soils 27storiesComments and questions regarding this article may be directed to the contact person listed on this page.