From Country Boy to Scientist, an Unlikely But Fantastic Journey

By Lynnette Harris |

CAAS Dean Ken White with Zhongde Wang, Hua Wu, and USU President Noelle Cockett.

There are turning points in every life that, especially in hindsight, mark the point at which everything changed, an event that sets someone on a path they could scarcely have imagined before. Professor Zhongde Wang noted one such pivotal moment in his life during the Inaugural Lecture celebrating his promotion to professor, with a slide that read, “An unexpected but great turn in my life—all because of the generosity of a family friend.”

That unexpected turn and generosity made Wang not only the first person in his family to attend a university, but the first person from the village where he grew up to attend a university. Wang was raised in a remote village in northeast China, high in the mountains near the Russian and Mongolian borders. The village was established as a settlement for people, like Wang’s father, who worked as lumberjacks, harvesting timber that built communities in more hospitable parts of the country. And besides being known for lumber, the area was known for extremely cold winter temperatures.

“It is a beautiful place, but there were very few people there because the elevation makes it so cold,” Wang said. “It was famous for temperatures that could be -58 degrees Celsius.”

Because of the extreme cold, children in the village, including Wang and his five siblings, did not go to school during the long, cold stretch from late fall to spring. Despite the lack of early formal education, Wang was a very curious child and loved learning and exploring. He was a young teen when a friend that his father had not seen or communicated with in more than 20 years came to the village to buy lumber for a large building project at a high school where he was the principal. The man had been a math teacher and while he was at the Wang’s home, he gave Zhongde a few math problems to work.

“I solved them and he told my parents he thought I could do well in school and that I could come live with his family and go to his school,” Wang said, and laughingly added, “And my parents think, ‘We have six kids, so, yes, take one.’“

So Wang made the move even though it put a distance of 30 hours by train between him and his home. At his new school, he was sometimes taught by former university professors who were among the intellectuals who had been forced from their jobs during the Cultural Revolution. It was some of those teachers who encouraged Wang and other promising students to take a university admission exam. Wang was among the several students in his class who moved on for more education.

Attending the university was another important event for more than intellectual reasons. Wang met his wife, Hua Wu, when they were lab partners in a chemistry course. They celebrated their 30th wedding anniversary last year. After graduation, Wang worked as a research assistant and completed a master’s degree in biochemistry. His education path then brought him, his wife and daughter to the U.S., where he earned a PhD in molecular and cell biology at the University of Massachusetts-Amhurst, and then did post-doctoral work at MIT.

The family had grown to love the American lifestyle, and a colleague contacted them with a job offer for Wang and another for Wu, who had also completed advanced degrees, at SAB Biotherapeutics in South Dakota. The family made the move to Sioux Falls and went to work at the biopharmaceutical company founded and led by USU alum Eddie Sullivan. Wu is now the company’s senior scientist and vice president of vaccine and antibody development and an adjunct faculty member in USU’s Department of Animal, Dairy and Veterinary Sciences. The opportunity to come to USU in 2012 with USTAR support drew Wang to the College of Agriculture and Applied Sciences, and the couple now generate a sizeable amount of frequent flyer miles between Utah and South Dakota. They have also become expert at using Skype and stay connected to family members in many locations almost daily, including their daughter who practices law at a large firm in Washington D.C. after having earned degrees at Harvard and Yale.

On a visit back home several years ago, Wang presented his parents with a tablet and was giving them instructions about how to use it, which was not a completely smooth process. Some youngsters in the room voiced their doubts about whether their great-grandparents could learn to use the technology and master Skype, “and that was all the motivation my father needed,” Wang said. He virtually visits with his parents—who are both in their 90s and celebrated their 73rd wedding anniversary last year—several times each week.

Since arriving at USU, Wang has run a very busy laboratory and had many successes discovering ways to understand and combat diseases. Genetically modified mice have long been the most widely used animal models for studying diseases that impact humans, but mice have severe limitations.

“Mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases and we decided mice needed a better sidekick in the lab,” Wang said. “Hamsters are better models for many cancers, metabolic syndromes and infections.”

Using CRISPR/Cas9 technology to produce the world’s first gene knockout hamster that is now used as a model for learning how a number of diseases progress. Wang and Rong Li, a post-doctoral fellow working in the Wang lab, were among the co-authors on a paper published in Nature last November, that demonstrated how hantavirus infects cells to cause disease that is sometimes fatal.

Wang’s lab is turning its attention to some other animal models, including naked mole rats, and he does not try to contain his excitement and enthusiasm for their very unusual characteristics. They are the longest-lived rodents, with a lifespan of up to 30 years, which offers many new possibilities for longer-term studies. In addition, they do not develop cancer, in fact, they appear to be resistant to the disease. They are social creatures who work together in extensive tunnel networks. Worker mole rats spend most of their time constantly digging, to create spaces for their colony, while other mole rats very effectively defend the colony from predators. Wang and the student researchers in his lab look forward to learning more about the creatures, and especially their apparent unsuceptability to cancers.

Professor Wang's parents and siblings.

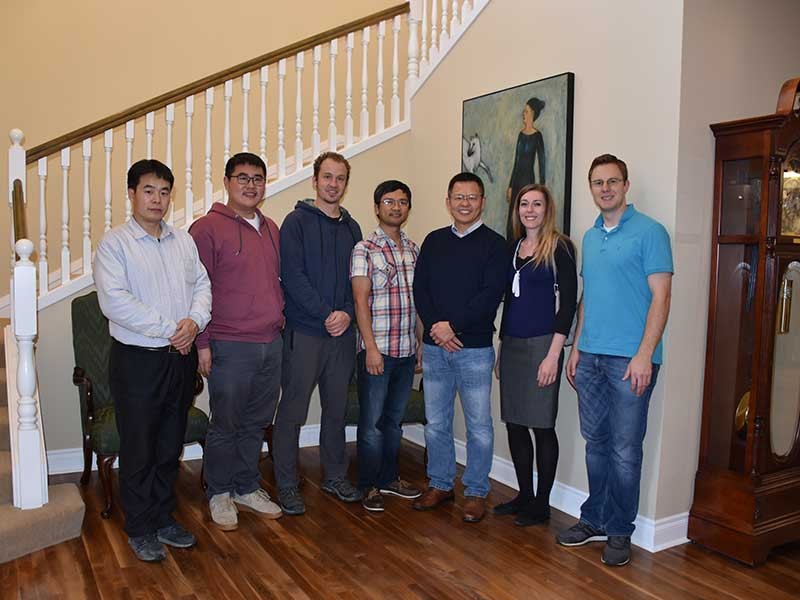

Professor Wang with some guests from his lab at the inaugural lecture (left to right): Honggua Cao, visiting professor; Yanan Liu, postdoc; Nick Robl, DVM, PhD student; Rong Li, postdoc; Professor Wang; Jacki Kurz, assistant professor in ADVS and former PhD student in Wang's lab.

WRITER

Lynnette Harris

Marketing and Communications

College of Agriculture and Applied Sciences

435-764-6936

lynnette.harris@usu.edu

CONTACT

Zhongde Wang

Professor

Animal, Dairy, and Veterinary Sciences

zonda.wang@usu.edu

TOPICS

Faculty 308stories Inaugural Lecture 129storiesComments and questions regarding this article may be directed to the contact person listed on this page.